Liz Blazer, Celebrity Deathmatch Animator, Author and Educator, on the SOM PODCAST

Animated Storytelling with Liz "Blaze" Blazer

Liz Blazer was a successful fine artist, but the fine art world wasn't for her. She chose to blaze her own path, telling stories through animation — like Ozzy Osbourne fighting Elton John to the death.

Now a famed filmmaker, art director, designer and animator, Liz has worked as development artist for Disney, director for Cartoon Network, special effects designer for MTV, and art director for Sesame Street in Israel. Her award-winning animated documentary Backseat Bingo was shown at 180 film festivals across 15 countries. But that's not all.

Liz is the authority on animated storytelling. She wrote the appropriately entitled Animated Storytelling, now in its second edition, and currently teaches visual arts at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she emphasizes the art of storytelling in pitching and delivering successful animation projects.

Our founder, CEO and Podcast host Joey Korenman raves about Animated Storytelling (and its illustration, by Ariel Costa), and makes the most of his opportunity speaking with "Blaze" on Episode 77.

During her hour-long appearance, Liz speaks with Joey about her transition from fine art to animation; the importance of movement, breath and soul in art; animation's ability to "charm" and "suspend belief;" the creation of her award-winning animated documentary; how she ended up writing a book by accident; the differences between animation and motion design; the keys to compelling storytelling; and more.

"I wanted to write a book for my younger self that was inspiring and simple and clean, and I wanted to write a book for a practical type who can't wait to get moving on their latest brainchild, and just needs tangible guidance to get there." – Liz Blazer, on her book Animated Storytelling

"There's only so many days you can go to work and sculpt Ozzy Osbourne to fight Elton John, knowing that he's going to bite off his head." – Liz Blazer, on animating for MTV's Celebrity Deathmatch

Liz Blazer on the School of Motion Podcast

Shownotes from Episode 77 of the School of Motion Podcast, Featuring Liz Blazer

Here are some key links referenced during the conversation:

PIECES

- Rechov Sumsum

- Celebrity Deathmatch

- Tolerance PSA

- Marilyn Mason - "My Monkey"

- Backseat Bingo

- HBO logo

- MTV logo

- PSYOP's Happiness Factory for Coca-Cola

- Chipotle re-brand

- The Wisdom of Pessimism by Claudio Salas

ARTISTS/STUDIOS

- Ariel Costa

- Rony Oren

- Joshua Beveridge, Head of Animation, Spiderman: Into the Spider-Verse

- Buck

- Justin Cone

RESOURCES/OTHER

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Ænima

- The USC School of Cinematic Arts

- Motionographer interview with Liz Blazer

- After Effects

- Nuke

- Flash

- iPhone 11 Pro

- CalArts

- Blend

- Google Fi

- Fruitopia

- Motion Design Education (MODE) Summit

- Tex Avery

- The Animator's Survival Kit by Richard Williams

- Preston Blair

- Amazon

- Six Word Memoirs with Larry Smith

- Ernest Hemingway's six-word story

- Avatar

- Instagram Stories

- Memento

- The Crying Game

- Charles Melcher and Future of Storytelling

The Transcript from Liz Blazer's Interview with Joey Korenman of SOM

Joey Korenman: My guest today is an author. That's right. She wrote a book, and it's a pretty awesome book, if I may say so. The second edition of Animated Storytelling has been released, and I read the whole thing, and I got to say that I was not expecting to learn as much as I did. I'm kind of cocky, and I figured, I know how to tell a story, and I know how to animate. Well, it turns out I didn't know nearly as much as I thought I did. Thank goodness for Liz Blazer who had put together an informative, inspirational, and very entertaining book that goes deep into the concepts and techniques of storytelling.

Joey Korenman: The book is also very beautiful to look at because Liz brought on Ariel Costa to do the cover and many illustrations throughout. Liz asked me to write a blurb for the back cover of the book, and I insisted on reading it first before agreeing, and I have to say I am honored to recommend Animated Storytelling. It is really a great resource. I have no financial interest in saying this. It's just an awesome book. In this episode, we meet Liz 'Blaze' Blazer, and she's got quite an interesting resume. She's worked on Rechov Sumsum, the Israeli-Palestinian Sesame Street. She worked on Celebrity Deathmatch. You remember that MTV claymation wrestling show? It was really bloody. I sure do. She teaches, which makes me a huge fan, and I promise you that after this episode, you will be too.

Joey Korenman: Liz Blazer, your name is so cool, by the way. Thank you for coming on the podcast. I cannot wait to talk to you about your book.

Liz Blazer: Thank you for having me.

Joey Korenman: Right on. I will say Blazer sounds a little cooler than Korenman, so I'm a little jealous right off the bat.

Liz Blazer: I apologize. I apologize I am Blazer. I've been called Blazer throughout college, and Blaze, and I will never give up my name.

Joey Korenman: All right, Blazer. Well, let's start by just sort of introducing you to the School of Motion audience. I'm sure a lot of people listening are actually familiar with you because your book. Animated Storytelling has been out for a little while, and we're going to get into the second edition, which was just released. But I was doing my normal sort of Google stalking that I do for all my guests, and you've got a pretty crazy resume. You've worked on some things that I cannot wait to hear about. So, why don't you kind of just give everybody the brief history of your career?

Liz Blazer: Okay. Brief history of Liz. My 20s were about artistic experimentation and wanderlust. I studied fine art in college, and when I graduated I was represented by an art gallery, which was really lucky for me because I had cash and freedom, and it funded a lot of adventure. I spent a year in a Prague with a site-specific performance troupe, and when I returned from that, I applied for an artist residency in the Negev Desert in Israel. While there, I was in the studio, and I kept seeing my paintings and these mixed-media photographs moving in my head, and became obsessed with that idea, that it needed to move, and this idea of wanting to animate.

Liz Blazer: So, after a year, I moved to Tel Aviv, and I needed a job, and I started applying, and was kind of focused on animation companies, and finally found an interview at a place that specialized in clay animation, which was super exciting because clay animation is rad, and I always loved it. So, I was very excited when the art director explained that their model maker just gave notice, and asked if I wanted to do an art test. So, he picked up one of their biblical characters from a set, handed me five different-colored lumps of plasticine, and said "Copy this."

Liz Blazer: I worked for a while, and then he said, "I'm leaving. Stay until you're done, and just pull the door closed behind you." I stayed for hours and left a tiny note in the character's hand that said, "I can work tomorrow," and my number at the bottom. I was shocked that I actually could do it, but also relieved because I thought, "Wow. Maybe I'm going to be able to animate now." He did call the next morning. He said, "You're hired," and I began model making, then character designing, and finally art directing for the Palestinian-Israeli Sesame Street.

Joey Korenman: Wow. Okay. I wrote down so many things. So, let's start here. You-

Liz Blazer: You said brief. You said brief, and then I just got started.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. Yeah, and I feel like there's more, but that was a good place to stop. Okay. So, you studied fine art, but then you eventually decided you didn't want to do fine art anymore, and I've actually heard that from a few guests. I'm curious, what was it for you? Were you sort of driven away from fine art, or were you more kind of sucked into animation?\

Liz Blazer: You know, I always loved animation. I didn't realize that it was a possibility for me, I think. I had success in fine art, and when I realized who the audience was, I was like, "Whoa, this is not for me." The art audience... I mean, I sold art. I had a gallery that was looking, and a director that kept coming, and, "Oh, this will work. Oh, that wouldn't work, and this one sold, and that one..." I was like, "This is just not where it's at." I just after a while felt like I was faking it, and I just didn't care. I think also, this natural desire to tell stories and time-based media, I had some experience in theater and in performance, and I was longing for that opportunity to reach an audience with time.

Joey Korenman: This is kind of interesting because I have some questions later on I want to get into about the difference between sort of the traditional animation industry and the motion design industry, or really even just between those two formats, and you're kind of bringing up this other idea, which is that there is... I mean, all of it is art in some way, and fine art has this different thing about it than sort of commercial art, which is more what animation is. So, in my head, when you were talking I was kind of picturing the stereotype of pretentious art critics wearing really expensive glasses and turtlenecks, and that's not really my scene either. I mean, is there any truth to that stereotype? Is that sort of why you felt like it didn't fit?

Liz Blazer: No. I love art. I just took my students to The Met. We had a great day. I'm an art lover. I just felt like it wasn't my place, and I wasn't driven to do it. I just felt like I had so much more interest in human stories and in life and in... I just felt like it was too deep, and it was also too boiled down to one solid, quiet moment, and it didn't have time, and it didn't have movement. There was no movement, and it was dead. Also, this whole idea of anima, soul animation, anima, the Latin... The first time I animated, I remember that poof, that breath that came out, like it was breathing, and you have this God complex, like, "Oh, my god. It's alive," and that's it. You're done. You've done it.

Joey Korenman: It is like a magic trick, yeah. Yeah. Ænima's also my favorite Tool album, by the way. So, I want to talk about Rechov Sumsum. So, you mentioned the Israeli-Palestinian Sesame Street, and I remember... I've actually seen episodes of that when I was young and went to Sunday School. They would sometimes show us those things. So, what sort of things were you doing on that show?

Liz Blazer: That was complex, man. It was canceled. The whole idea of reach the children and reach love, and let's show each other what we have in common, not what we have different. So, it would be like you'd have Mohammad and [Jonaton 00:09:21], two kids named John, and [Ima 00:09:25] and Mama, two moms, and they would play in the park, or you'd just have these situations where they... First of all, they couldn't live on the same street, so there was not one Rechov Sumsum. They each had their own block. They had to be invited. It was really complicated. It was a great idea, but because of the crazy politics over there, it just... I can't even talk about it, to be honest with you, just because the region is so upsetting, and the show had really beautiful objectives, but it's just so sad to me that a TV show can't solve a problem as big as the conflict.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. I mean, that must have been pretty heavy, and I looked on your LinkedIn to find out what years you were there, and I think you were there during the first Intifada, or maybe right before?

Liz Blazer: I was there second.

Joey Korenman: The second? Okay. I mean, there was some very serious violent conflict going on.

Liz Blazer: I think. Well, I was at the assassination of Rabin. I was there.

Joey Korenman: Oh, wow. So, you must have felt a lot of responsibility working on that show, to-

Liz Blazer: I mean, you just feel lucky, and you want to do the best you can. I mean, at the end of the day, I was as thrilled to be close to Kermit as I was close to making something meaningful and powerful and wonderful, but it was... Our hands were tied, like any production.

Joey Korenman: It's interesting because animation has this power of reaching especially children. I mean, it's kind of a unique medium in how it can communicate directly in terms of the id of a little boy or little girl. So, that was an early experience for you. I mean, as someone who wanted to get into animation, what were your goals at that point, and how were you kind of taking all of it in and thinking about this in terms of your career?

Liz Blazer: So, I really loved... I worked on a public service announcement when I was there also that was called [Foreign language 00:11:33], which is tolerance, and that was an animated documentary that was modeled after creature comforts. I worked with this absolutely brilliant animator, Ronny Oren, and they interviewed people all over the region that were just talking about different takes on patience and tolerance with different people, and that was really instrumental for me with Rechov Sumsum, wanting to make content that had a positive and teaching, healing ability, and knowing that this medium could reach people, create discussion, create change. So, I came back to the US, and the polar opposite thing happened. I had came back to New York. I was looking for work, and I went on two interviews. The first was for Blue's Clues-

Joey Korenman: Nice.

Liz Blazer: ... and I didn't get that job, and then the second was for Celebrity Deathmatch. Just when I thought I was going to hopefully work on children's programming or something, edutainment, it was like, "Your job is to make the heads the most extreme head increments before a character dies." So, I have to say, it was a lot of fun, and it was a wild ride.

Joey Korenman: That show is... There are episodes of it still up on YouTube, and that came out, I think, while I was still in high school, and so it just brings up all this nostalgia of MTV making cool things instead of The Hills or whatever they do now.

Liz Blazer: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, for me it was like this stop on the bus for me. I loved working on that show. The people that worked on that show were so amazing and so talented and so fun, but after a few seasons, that's when I went to grad school, because I was like, "Okay. If I'm going to do... I need to learn more about this medium because I can't work on shows like this for the rest of my life." I knew that shows like that weren't going to exist for the rest of my life. But it was a lot of fun.

Joey Korenman: How did you know that?

Liz Blazer: I mean, there's only so many days you can go to work and sculpt Ozzy Osbourne to fight Elton John, knowing that he's going to bite off his head.

Joey Korenman: I want to put that on a t-shirt.

Liz Blazer: Oh, and then what happened? Oh, and then the queen comes in and gives him the Heimlich maneuver, and then he goes, "God save the queen." I mean, it was like, this can't last forever.

Joey Korenman: So, your book is called Animated Storytelling. I mean, this is a form of storytelling, right? So, I'm curious. How involved were you in the actual storylines of these things, or were you really just sort of sculpting spines and things like that?

Liz Blazer: Not at all. Not at all. I mean, we would come up with designs that solved the problems that were in the script and storyboards. So, like any production, you have a pipeline, and my job was with my friend Bill, who was helping... He was designing in 2-D, and then I was interpreting into 3-D, usually making incremental heads or the extreme pose that the animator would pop on, so it would hold on that head in the most extreme exploded or decapitated or disemboweled, or whatever the most... So, you would come up with the design or talk about how that was going to happen, but I wasn't writing it, not at all.

Joey Korenman: I just had so much love for that show. At the time, it sort of checked all the boxes. I was into kung fu movies and ridiculous, silly, surreal stuff. I remember watching Charles Manson fight Marilyn Manson and thinking, oh, this is pretty brilliant. So, it's really cool to meet someone that was associated with that. Yep.

Liz Blazer: Yep. I worked on that episode, and we worked on the video with the monkeys. Did you see that Marilyn Manson video with the monkeys?

Joey Korenman: If you tell me what song, I'm sure I've seen it.

Liz Blazer: I don't remember. I just remember sculpting a lot of heads and monkeys.

Joey Korenman: Interesting. It's funny because everyone pays their dues in different ways, and you've sculpted monkeys and blood and brains and things like that.

Liz Blazer: Oh, man. You have no idea.

Joey Korenman: Oh, it's My Monkey, I think is the name of the song. I just Googled it. All right. Well, here. Let's talk about more sort of serious matters here, Liz. So, you also-

Liz Blazer: Yeah. Not my favorite.

Joey Korenman: You also made a short film and sort of did the festival circuit and all of that. I'd like to hear a little bit about that. So, could you just tell everybody about your film?

Liz Blazer: So, my film was called Backseat Bingo. It was an animated documentary about senior citizens and romance, and it was my master's thesis as USC film school. It was an homage to seeing my grandfather fall in love in his 80s after being married for 60 years to my grandmother. He fell in love so deep and so hard, it was like watching a teenager, and I'll never forget seeing hair grow out of the top of his bald head, and him wanting to talk about having sex. That's what inspired... It was amazing, seeing him come back to life through romance, and what a stigma it was. My mom didn't want to hear about it, and a lot of people thought, ew. Nobody wants to hear about an old person having sex.

Liz Blazer: For me, it was like, what more would you want to hear about? It's so life-affirming, and just because they're old doesn't mean anything different than they're young. It's the same package. So, that was what created the desire to make this film, and it was a long journey finding a group of people who wanted to be interviewed, and then turning it into animation. But the bigger question for me was why I made a documentary, and why make it so simple? I think that at that time at USC film school, I was surrounded by serious talent. It's not that I felt talentless. I just knew where my talent was, and I knew that I wanted to really capitalize on story, and focus on asking questions about how you tell a story and what tools you have at your disposal.

Liz Blazer: For me, getting the documentary done was as much of a project or more than the animation. Finding the subjects, befriending them, interviewing and editing was huge amount of work. Then the character design and animating was actually... It was just as much work, but I was sort of making a statement to all my friends who were 3-D wizards, that were making these incredibly gorgeous 3-D films, and some of them didn't do as well as my film because they were more focused upon the flash and the bell and the whistle than the underlying story, and I feel like this film for me was just like a big experiment in what happens if you make the simplest animated thing with the biggest heart.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. You just kind of summed up, I think, the biggest challenge that new motion designers face, which is it's easy to get caught up in the style over the substance, and that actually leads perfectly... This is a great segue, Liz. Thank you. All right. So, let's talk about storytelling, and I wanted to start with this awesome quote that I saw in a motionographer interview with you. I think this is when your first book came out. So, you said, "A storyteller should use animation because it's limitless, both in its ability to achieve the fantastical, and in its fantastic ability to charm an audience."

Joey Korenman: So, you were just talking about why... If you're making a documentary about the sex lives of senior citizens, you could just get a video camera out and just go shoot them, but you decided to use animation. It gives it this charm and this vibe that it wouldn't have had if you really saw aged skin and all of the things that happen when you turn 80. I want to hear a little bit more about this idea of animation having this ability to charm an audience. So, why don't we start there? Because I have some more I want to dig into. So, in terms of using animation as a medium, how do you see the strengths of it versus, say, just getting a video camera out and shooting something?

Liz Blazer: So, animation has a certain nature to this medium, in that it's limitless, and anything is possible because there's no gravity, and there's not physical laws that apply to shooting an animated film. So, our job becomes to build a new world, a new language, a new visual language, and to take our audience on a journey, and perhaps even take them on a journey that they've never imagined, they've never seen, and that journey could be a visual journey, an emotional journey, a high-concept journey, but this medium gives you something that no other medium gives, and that is completely suspended belief. You enter, and anything can happen.

Liz Blazer: So, I think you have a responsibility when you start with this medium to first say, "Well, can this be done with live action? Why is it animated?" We say that all the time when we're working, is, "Why is it animated? Why is it animated? What makes it special?" Right? Then the feeling of charm, I think that comes from a responsibility to the history of the medium, and for over a hundred years, there's been a push and pull between character and experimental, but I think that we really owe a lot to the history of character animation and the principles of animation and this idea of appeal, regardless of whether it's character, experimental, or motion graphics. If it's animated, there's got to be some charm, some warmth, some relatability.

Joey Korenman: What does appeal mean to you? Because that's one of those principles where it's like, I don't know, you kind of know it when you see it or something. Do you have a way of thinking about it?

Liz Blazer: It's so hard. It's so hard. It's so hard. It's visceral, right?

Joey Korenman: Yeah.

Liz Blazer: It's got to be warm. It's got to be human. It's got to be relatable. This is a question I always deal with, and it's like, you know we all relate and enter on certain emotional notes. It can be sound, man. It can be a sound. You hear a baby cry, and you see a blanket. There are certain ways that you can bring an audience in with charm. Hard to explain.

Joey Korenman: Yeah, yeah. Okay. So, let's kind of talk about this in a different way. So, your quote was talking about animation as this limitless medium, and I love how you kind of said... I think you said that you can completely suspend disbelief. Right? You can have a universe where the laws operate any way you want them to, and that's really cool. You can go mad with power. But also from a business standpoint, because I've always been into motion design industry. I've never been in sort of the traditional storytelling animation industry where it's a little bit more about the story you're telling than the message you're communicating or the brand you're promoting.

Joey Korenman: Animation always had this really great sort of value proposition, to use a really gross business word for it, where production was traditionally very, very, very, very, very expensive. The barrier to entry was really high, and you could get After Effects, and you could kind of make whatever you want, provided you had the chops, and I got into the industry in early 2000s, and you're probably around the same time. So, do you think that anything's changed with regards to that? Is animation still... Does that value proposition that you said, it's limitless, you can make anything you want, does that still help sell that idea to clients in 2019 when you can also buy a really bad-ass camera for 500 bucks, and then basically shoot anything you want?

Liz Blazer: I'm not even sure I understand the question. I feel like this is an idea of building a world, and it's a conceptual idea, and I'm not certain that that's dependent on the cost, because you're selling a concept, and I feel like we get really caught up on how big the fire is, and well, is it Nuke, and is it explosions, and are there robots, and you can make really simple robots. I'm not sure I understand the question.

Joey Korenman: Well, I guess, think of this way. So, if someone commissioned you to make Backseat Bingo, and back when you made it, and if you wanted to do a live-action version of it, you'd need a camera crew and lights, and then all this post-production, this and that. But the way you did it, I'm assuming... Did you do it in Flash or something like that?

Liz Blazer: No. That was in After Effects.

Joey Korenman: That was in After Effects? So, really beautiful and really warm kind of design and art direction to it, but very, very simple execution.

Liz Blazer: Simple.

Joey Korenman: Simple, simple. You could've used a tape recorder or an iPhone with a recorder or something like that. So, that's always been, in my experience, anyway, one of the value propositions of animation, is that you can still get that emotion you want out of the viewer, but you don't have to have hundreds of thousands of dollars of gear and a giant crew. But in 2019, things have gotten so much simpler. I mean, the new iPhone shoots 4K video and has depth of color, all that stuff, so yeah. So, I'm curious if that changes anything in your mind.

Liz Blazer: Well, I do think there's an amazing thing that's happened, which is these [autours 00:25:48], these one-wizard shows have more and more capacity for their voice to be heard, and I love that. I'm a huge fan of Ariel Costa, and people like him make a huge splash, because not only the materials are cheaper, but they can get a lot done faster.

Joey Korenman: You brought up a really good point just now. I never really thought about it that way, and Ariel Costa's a perfect example. When you're doing animation, you can do it all by yourself, and he's a unicorn. He's an amazing designer and an amazing animator, and he's a brilliant conceptual thinker, and that lets him be an auteur. It's his singular vision, which I think is harder to do in live action, because even the smallest-

Liz Blazer: Oh, totally.

Joey Korenman: ... shoot requires a crew. Yeah.

Liz Blazer: But a lot of these companies that we see, they're driven by one or two people, and you see them all over, and they have a look and feel that is very, very specific, and that's what's so exciting, I think, about motion versus sort of the world of animation in the bigger studios. The bigger studios, they're like, "We do A, B, C, D, and E," but the smaller studios, you're going to them because you're really getting this streamline that's coming out of just a few people, and I think that's where the value comes in, is they can operate much lower overhead.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. Okay. So, you started in Israel working in claymation, and then you go to New York, and you're working on Celebrity Deathmatch. When did you become aware of motion graphic as sort of a separate thing?

Liz Blazer: I always loved motion graphics. I don't know that I knew it was called motion graphics, but I loved title sequences and broadcast graphics and commercials for as long as I can remember, and I'm older than you. So, we were the first on the block to get cable, and I remember when MTV and HBO first came out, thinking the best job in the world is to make those identities. The MTV logo when it first came up, I was like, "That's what I want to do."

Joey Korenman: Spaceman.

Liz Blazer: The spaceman, and then HBO, there was this identity where the camera flew out of the bedroom and then over the model, through the town, and up through the sky. You remember...

Joey Korenman: It's famous, yeah.

Liz Blazer: I was like, "Yeah, that looks like fun. I want to build that city." So, that's my first awareness. I don't think I knew it was called motion graphics, but I think I always knew that title sequences were called motion. When I was in graduate school at USC, it was kind of a sad awareness when I said to somebody, "Oh, I'd really like to do title sequences," and they were like, "Oh, that's motion graphics." It was like, "Oh, is that not what we're doing here?" The distinction blew my mind, that somehow this was not animation.

Joey Korenman: Was it seen... It's interesting because there's still a little bit of a debate as to is there even a difference between animation and motion graphics or motion design, what we typically call it now. I'm assuming back then your faculty would've said, "Yes, there's definitely a difference." What was sort of the vibe back then?

Liz Blazer: Back then, it was like, "Well, if that interests you, you should go talk to that guy. That's what he does, and that's not what we're teaching." It was sort of like it was commercial or lesser, or we're prepping you to work at Pixar or Sony or... It was lesser. It was not what they were doing. It was commercial. It was flying text. They thought of it as graphic design moving that was not an art form. That's what I gathered, and I thought it was completely crap. But I also don't understand the difference between experimental and character, and to this day, one of the greatest programs in the world, CalArts, has character and experimental very separate.

Joey Korenman: Interesting. I just came from a conference in Vancouver called Blend, and-

Liz Blazer: I love it.

Joey Korenman: Yeah, it was amazing. One of the speakers was the head of animation on Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, and he was talking to one of our alumni, and he comes from the traditional sort of character animation, feature film world, and he was speaking at a motion design conference, and I think he said something to the effect of, "We were trying to be experimental on that film, but you guys," meaning the motion design community, "are all experimental. That's where we start."

Liz Blazer: That's right.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. So, maybe that's a good way to get into this question, and this is something I'm thinking about a lot right now, is what the hell is motion design? What makes it different from animation? Is there a difference? So, I'd love to hear if you have any thoughts on that.

Liz Blazer: Well, I don't really get it, to be honest with you. I've seen some really weird definitions out there. For me, in its simplest form, I feel like motion is when you have something to tell or sell, and there's sort of a creative brief that you are delivering. I think there's a lot of gray area, and I think that a lot of motion artists are doing the exact same thing as animation half of the time, and half of the time they're doing motion design. So, I just feel like it's based upon the project and the client.

Joey Korenman: So, maybe more about the intent of the work?

Liz Blazer: I feel like, yeah. I mean, Ariel Costa, half of what he's doing is animation, and then when somebody calls him up and says, "I want you to do this infographic that explains this for this reason," it turns into motion design.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. I mean, I think part of the challenge is it's hard to reconcile someone at Google animating little shapes for a UI prototyping project or something like that versus someone at Buck doing a full-blown, feature-film-quality 3-D animation for a spec project, and saying that those two things are the same. Right? They're both motion design. So, everyone in the industry kind of struggles to define it and to tell their parents what it is they do for a living.

Liz Blazer: How do you define it?

Joey Korenman: Well, the way I-

Liz Blazer: I'm really curious.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. So, it depends who I'm talking to. So, if I'm talking to my mom, I usually say it's animation, but not what you're thinking of, not Disney, not Pixar. Right? Animation plus graphic design, logos and things like that. I sort of talk around it. What I've started thinking, and it really, I think, mirrors a little bit of what you said, is that it's about the intent. So, if the goal is to tell a story, and that's the goal, and that's what films are, that's the goal, a film is telling a story, a TV show is telling a story, a short film is telling a story, then that feels like animation to me, even if it's not characters, even if it's little dots that represent people. It doesn't feel the same as using dots to talk about how Google Fi works, and it also doesn't feel the same if you have characters selling Fruitopia juice squirt boxes or something in this weird sort of world.

Liz Blazer: And you don't think that that's telling a story?

Joey Korenman: It is, but the point is not to tell a story. The point is to sell product or to explain how something works. I mean, that example I just gave is probably a bad one because to me that is kind of that gray area where it is a story, but in service of selling a product. So, I don't know. I mean, I don't have the perfect answer either.

Liz Blazer: I know. I know, and then I look at things like half of the infographics out there, well, the better stuff, I'm like, it's beautiful story. So, to me that is storytelling, and I see a lot of these definitions that say, "This distinction is story," and just kind of object to it. I feel like motion design is about story.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. That's actually one of the things I loved about your book, so we're going to talk about your book now. I love that because what you did a really, really, really amazing job of doing is breaking down storytelling, first of all, into some great examples, and even some processes you can follow, and some exercises you can do to help, but you also use examples of both, sort of what you traditionally think is a story, like this character wakes up, and they look out the window, and there's a problem, and you used examples that are very, very motion design-y, and you did a really good job of translating it into words that someone who might be animating logos all day can still get value from.

Liz Blazer: Well, thank you.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. So, let's get into your book. So, the book is Animated Storytelling. We're going to link to it in the show notes. Second edition just came out, and if you look on the back of it, you'll see two quotes, one from Justin Cone, and one from someone that no one has heard of. I want to-

Liz Blazer: You.

Joey Korenman: Well, it was me, and thank you, by the way. It was a huge honor. So, this is the second edition. The first edition was published 2015. So, let's start with a question that... I'm sure you've gotten this before, but why write a book?

Liz Blazer: Why write a book at all?

Joey Korenman: Yeah, why write a book? Well, I can frame it for you. Animation, right?

Liz Blazer: Right. Good stuff.

Joey Korenman: Moving pictures, visuals. Why a book?

Liz Blazer: Okay. That's a good question. So, it never occurred to me to write a book. That's why I'm stumped by the question. I'm not a writer.

Joey Korenman: It was an accident, actually.

Liz Blazer: Yeah. The opportunity arose organically. I was developing a whole 10-step theory in the classroom, and it was something that I presented at a presentation at MODE, the Motion Design Summit, and a colleague said, "Your presentation would make a good book," and introduced me to her publisher.

Joey Korenman: Wow.

Liz Blazer: It was like, I got into this mess because I don't like writing. Then I spoke to the publisher, and I just know an opportunity when I see it. So, within a month, the proposal was accepted, and I had a really quick deadline to write a book. So, I had to write a book. So, I never thought to myself, "I'm the writer of a book, and I have so much to say," but once it came to pass, I wanted to write a book for my younger self that was inspiring and simple and clean, and I wanted to write a book for a practical type who can't wait to get moving on their latest brainchild, and just needs tangible guidance to get there.

Joey Korenman: Well, I think you nailed that, and the book is... I'm looking right now. So, the second edition, it's about 200 pages, it looks like. It's not super long. There's lots of pictures. It's probably a two-or-three-poop book, and it's amazing. It's also-

Liz Blazer: Did you just call my book a two-or-three-poop book?

Joey Korenman: Well, sometimes... Because everyone reads at different speeds, and so that to me is just kind of one metric you can use. You could use a different one. You could say-

Liz Blazer: Oh, that is terrible.

Joey Korenman: I mean, you don't think people will read it when they're going to the bathroom?

Liz Blazer: No, no, no. Uh-uh (negative). We're just going to move on. So, I live in New York. I made the first one way too small because I wanted it to be intimate, and I wanted it to be a book that was like was whisper of encouragement, and that you could take with you on the subway, and then it was too small. I couldn't see it, and I forced myself to make it too small. It never occurred to me that it was a one-poop book.

Joey Korenman: It might've been. I mean, everyone's different, but... So, the book is beautiful-looking because-

Liz Blazer: Thank you.

Joey Korenman: ... first of all, there's a lot of really great examples and frames and stuff like that, but it's also got a lot of custom design done by Ariel Costa, and I'd love to know, how did he get involved with this, and how much direction did you have to give him to get what you got out of him?

Liz Blazer: I met Ariel at a conference, and we were fast friends. I met him before seeing his work, which was lucky for me because if I met him after seeing his work, I would've been totally intimidated. So, we were talking about Tex Avery and really old... We were just riffing, and we were just having a gay old time, and then later, I think I was texting him on Facebook or... I didn't see his work, and then I saw his work, and I was like, "Oh, shit."

Joey Korenman: He's pretty good.

Liz Blazer: "This guy is the real deal," and then we were friends already, and then the book came up, and he's just the nicest person on the planet, and the sweetest. So, I had money for the cover, but nothing else. So, I was like, "Dude, please do my cover. I love you," and he was like, "I would love to. Thank you for asking me." I was like, "What? You're Ariel Costa. You're Mick Jagger." I was like, "I also would really love if you would do... How much would it cost? I'll pay for it out of my teaching budget." He was just game, and he was like, "This is great. I love it." He was like, "It would be an honor. I want to teach." So, it was just a synergy, and I just kind of told him what I was thinking, and it was fast and easy and beautiful.

Joey Korenman: You know, you reminded me of something that we were talking about before we ever started recording, and how you can kind of feel someone's heart through their work a little bit, and especially if it's in the written form, and your book, it's like a conversation with you. It's just this friendly, fun, helpful thing, and I'm curious if that was something you set out to do, or is that just sort of how you write? Because it sounds like you're a professional author, reading the book. I mean, it's really, really, really well-written.

Liz Blazer: Thank you. That is my husband. He's just the best editor, and he's the nicest person, and he pushes me to be clear, and my goal from the beginning was that this book would be a nurturing, unintimidating whisper, and it's also my teaching style. I like being warm and funny and open, so I tried to have my personality come alive a bit, but it was definitely my husband's blood, sweat and tears helping me get it kind of right. But I have a lot of books on animation, and when I was seeking answers, they were intimidating.

Liz Blazer: I love Richard Williams' Animator Survival Kit. I love Preston Blair, but they're big books, and they're big books of how to, and I wanted to write a book that was why, why we tell stories, why we make film, and that when you're done with it, you feel empowered, and you don't feel scared. So, I wanted the book to feel like a little whisper of confidence, and I wanted, when you read the book, to feel like I'm here for you, I'm your cheerleader, you can do this. Does that answer the question?

Joey Korenman: It does, yeah, and that's really beautiful too. So, tell me what's been updated and changed in the second edition.

Liz Blazer: So, I rewrote the whole thing. There's lots of tweaks from testing it in the classroom and testing it working with people and their stories. The new exercises that I developed are in it, and I wanted to do a deeper dive into nonlinear storytelling and experimental filmmaking, and help support filmmakers who are more process-oriented. So, I kind of rewrote the first two chapters, and then I wrote a new chapter, Chapter Three, which is Unlocking Your Story: Alternative Forms for Free Thinkers, which I'm really proud of because, again, this book, I could not find this book. I looked for it on the shelves and on Amazon. I couldn't find it, which is why I felt confident enough to write it, and then this third chapter about unlocking your story is something that I was always looking for to help me teach and help me communicate, and it's like this sort of idea that a lot of people are interested in linear storytelling.

Liz Blazer: They're happy with this idea that you have a setting and a character, and a conflict or a problem that gets bigger and that needs to be resolved, and that there's an ending. That's cool. We got that. But then there are people that that doesn't work for at all, and I'm probably one of those people. I think this speaks to motion graphics probably more. The experimental form is also a process-oriented form, and it's a form for those who may want to experiment with the tools and find a structure from what they're working on, and I tried to break it down into concepts.

Liz Blazer: One is using music as a structure. Another is starting with a piece of writing or poetry, and then dealing with sort of structures like repeating and evolving, which I feel like happens a lot with motion graphics, and then dealing with the last one I talk about, cut it out and play, which is sort of like doing and editing, and I think a lot of motion people do that. They're playing with the materials in editing. So, that's what's different about the book, is I really tried to do a much deeper dive into dealing with people that are process-oriented and who might be really uncomfortable with having a completely hashed-out storyboard.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. So, I think that is the thing I liked the most when I read the book, and I love the term process-oriented, because that kind of sums up a lot of motion design-y things that we do. One of the things that I used to believe was that you always had to start with an idea and flesh it out, and then do style frames, and then do storyboards, and then animate, and then there's a lot of artists that don't do that. They just sort of... There's some technique that they really want to play with, and so they'll play with it, and then they'll find a story in there, so it's almost like they're going backwards.

Joey Korenman: I think your book sort of... It's got some techniques to sort of help you do that, and also do sort of traditional storytelling. So, I'd like to talk about some of the specifics of the storytelling sort of teaching you do in the book. There are so many examples, so I really recommend to everybody listening to this, get the book. It's awesome. It's really great. So, I pulled out a few examples, and I'm hoping you can sort of give our listeners some stuff they can actually start trying. One exercise that I really loved was something you called the 6 Word Story, so I'm wondering if you can elaborate on that.

Liz Blazer: So, the 6 Word Story is not my idea. It's oldster. It's also Larry Smith's Six Word Memoir. You can go online and look at his website, which is rich with lots six-word memoirs. It started, I believe, legend has it, with Earnest Hemingway, and he was challenged to write a story in six words, and his response was, "For sale, baby shoes, never worn." There's a lot there. That's a full story. I feel like a lot of filmmakers have an idea, and it's foggy, and when they describe it, it's all over the place, and it's really three or four ideas. When you force them to do it in six words, it becomes one idea.

Liz Blazer: So, when I work with people, I'll ask them to make 10 six-word stories on the same story, and they end up going in different directions. The nature of them is that they're so brief that they force you to be clear, and the process helps you nail down... In some of them, they are the mood or the feeling, and in some they become the biggest plot point. So, then you rank them by which is your favorite and why, and so what happens is you end up going, "Oh. Well, it's got to be romantic, and it has to be about someone who lost their shoes." Well, in that case, it's a baby that wasn't born. So, it helps you find the core essence of what you're doing and stop waffling about all the unimportant stuff.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. It's a really, really great exercise to try and hone what is the point you're trying to make. Do you think that that technique of really trying to distill your idea down to six words, does that apply to commercial work if you're doing an explainer video for some software company?

Liz Blazer: Totally, totally. It's a tagline. It's forcing you... I always tell people, "Write it down on a piece of paper and hang it above your computer, and look up to it as you're working, because if you are clear that this is your goal the whole time you're working, every scene is going to be putting that feeling in there. You don't want to lose sight of... This is your overarching theme. Not theme, but you're moving toward this big idea." Because I knew you liked this, I have four more for you. Do you want to hear them?

Joey Korenman: Yes, please.

Liz Blazer: Married by Elvis, divorced by Friday.

Joey Korenman: I like it.

Liz Blazer: That would make a good short, wouldn't it?

Joey Korenman: Yeah.

Liz Blazer: This is not your captain speaking.

Joey Korenman: Whoa. These are so good.

Liz Blazer: She wasn't allowed to love her. Escaped war, war never escaped me. So, if you can boil it down to six words, you've got an idea. It's hard, but it's worthwhile.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. Okay. So, that was one of my favorite things when I read that. I was like, "Oh, that's so brilliant." Thank you so much for pulling those extra examples because it's amazing. I'm sure a lot of people listening are thinking, "Six words? How much of a story can you tell in six words?" You can tell this, almost an epic. I mean, there's so much-

Liz Blazer: Well, you can tell the heart. You can get to the oof of it, and if you know the oof of it, you can always make things more complicated. You can never make them more simple.

Joey Korenman: You know, you made me think of something. So, when you said that last one, I think it was she was not allowed to love her, in my head this entire two-and-a-half-hour movie just sort of manifested. Right? I'm seeing all these details, and Handmaid's Tale kind of thing. That's the way a lot of people's brains work. You don't need all the details. You want to leave something to the imagination. I'm curious how you think about that. How much do you want to tell the story versus how much do you want to hold back and let the viewer, in most cases, sort of have to extrapolate the rest out?

Liz Blazer: I mean, that's a case-by-case thing, but what I can say is that I think one of the biggest mistakes people make is in backstory and telling too much that doesn't really support the big emotional pull. So, she wasn't allowed to love her. They're going to give us too much about the first her or the second her that's not pertaining to this big conflict of what it... I would rather stay longer in scenes that support the tragedy than build to all these scenes that don't. Does that answer your question?

Joey Korenman: It does, yeah. It's a really good way of putting it. You're good at this, Liz Blazer. All right.

Liz Blazer: Oh, thank you.

Joey Korenman: My goodness. All right. Let's talk about another one that I thought was really, really cool, which is the yes, and rule. So, can you talk about that one?

Liz Blazer: So, the yes, and rule, again, not mine. Most of what's in my book I'm just channeling other people's stuff. Yes, and rules is a central rule of improv. It's about being positive and open. It's about trusting your instincts. It's about coming up with an idea and saying, "Yes," and building on it. It's about working and making mistakes, and not editing, and let ideas flow, and taking chances, and seeing what happens. So, yes, and, I'm going to go with this idea. Instead of closing up, no, but, no, but, just be yes, and, come up with something crazy, and go with it, and take the hour to go with it. You can reject it and edit later. 10% of it might be fantastic, and you may come up with that 10% in the last bit of your yes, and flow.

Joey Korenman: So, I'll ask you the same thing I asked about the 6 Word Story. I mean, is this something... I thought I recognized it as an improv thing, because I've heard that before. I've never done improv, but I've listened to podcasts where they talk about it. I can totally imagine something like this working really well if you're trying to make a short film, and you've got this crazy idea, and then you just sort of make yourself say, "Yes, and," and just keep going with it. Is this one that can also work in sort of more commercial work?

Liz Blazer: For sure. For sure. It's about world building. It's about any crazy idea, and I think that so many people are blocked because of self-judgment. So, if we throw... In my house, my husband and I are very supportive of each other's idea process. He's in TV, so he does this at work. We have these huge sticky notes. Everyone uses them, and you just start writing stuff up there, and you force yourself, more, more, more. Get it all out. It's all good. Then you circle what you like, and you cross out what you don't like. I feel like you can do this for the most commercial work to the most personal work. It's about being open, and it's about letting ideas come to the surface, and just trying out stuff.

Joey Korenman: You know, when you were talking about this, I was remembering, there's a really famous commercial done by a studio called PSYOP, and it's called The-

Liz Blazer: I love PSYOP.

Joey Korenman: ... Coke Happiness Factory. I'm sure you've seen it. That has to be one of those yes, and moments, like what if the inside of a vending machine is like the alien planet from Avatar, and there's these creatures, and it keeps getting weirder and weirder and weirder, and ends up winning all these awards and becoming this iconic thing. Maybe it's just because I've been in the industry too long and I'm starting to get jaded, but I don't see stuff like that as often anymore. Do you think that, I don't know, perceptually, have you noticed any sort of decline in that sort of willingness to go to weird places and just keep saying yes?

Liz Blazer: I don't know. I think it's a pendulum. I think these things spark up. I think that the limitlessness journey-taking element is... Right now, I don't see a lot of it in commercials, and I don't know if that's because of the budgets for commercials or where commercials are being shown or what's happening with digital and streaming. I think that we're in such a shakeup right now. As I said, my husband works in TV, and everything is... Until we see what's going to be with the cable networks and streaming, and where the ad sales are going, I think it's hard to see where the big budgets are. I think that if you watch just the Super Bowl commercials and analyze if there are these big journey yes, and animated ads, I don't know if there's less or if there's just less cool ads right now.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. This was another thing that came up at the Blend conference, and it was kind of a question. It was, is this... Because it does feel that way a little bit, and I think part of it is just everything's being diluted because there's so much advertising, and it has to be... Yeah, it's got to be spread out across a hundred different platforms.

Liz Blazer: And it's shorter.

Joey Korenman: Yeah, and story's hard, and story can be expensive. You know?

Liz Blazer: Yeah.

Joey Korenman: Coke Happiness Factory, I don't know if that's one of those projects that actually, the budget paid for it, or it was let's eat this one because it's going to be great on the portfolio, but I can't imagine commercials get budgets that high anymore. It's got to be very rare.

Liz Blazer: Yeah. I wonder. I mean, I think about Chipotle. That was such a different thing because it was a branding push that they were not even worried about running as ads.

Joey Korenman: Right, right.

Liz Blazer: Right? So, I don't know.

Joey Korenman: All right. Well, let's talk some more about story. So, you have an entire chapter on story structure, and I think most people listening have probably at least heard of the three-act structure, and there's also a lot of other options out there that are in your book, and you have examples, and it's really great. Some of those I think are super useful for motion designers where you have 30 seconds or you have 10 seconds, or it's an Instagram story, and you need to just capture someone's attention but tell a story, and that three-act structure can sometimes take a little bit longer. So, I'm wondering if you can just kind of talk a little bit about how you see story structure and some of the other interesting ways of telling stories that are in your book.

Liz Blazer: So, the three-act structure is beginning, middle, end. Right? Even if you're not doing a very deep dive, even if it's 10 seconds long, you can have a three-act structure. In the first two seconds, you can establish your world and your character or your figure, and then you can establish a conflict, that's something that has to change or be resolved, and then you can end it. So, the three-act structure applies, in my opinion, to content across the board, character or no character, even if it's a logo. You can have a logo enter that can't enter the frame, or appears like it's trying to get bigger. There are things that you can do formally that create that tension. Right?

Joey Korenman: Right.

Liz Blazer: Then from the nonlinear story structures, I guess my whole deal is that if you're going to make a piece, an animated piece, 10 seconds, 20 seconds, a minute, three minutes, be mindful that it has a structure. Be mindful that there tropes and that there are structures that have been used that are just natural in rhythm. It's musical, and it's math. If you support your story with those structures, your audience is going to be much more inclined to get it. So, I just give five in my book, simple nonlinear structures that you can apply over a three-act structure, or instead of a three-act structure, as additional support for your audience. Do you want me to go over them, or...

Joey Korenman: Yeah. I mean, I'd love to hear maybe one or two of them, because when you're doing... Everyone's always trying to stand out and do something interesting, and a lot of the work that we do as motion designers is either some form of a visual essay, which has to have some kind of structure to be watchable, or it's something really, really, really short-form where just keeping someone's attention and getting that message across has to be condensed. So, yeah, if you pick out a couple, and the movie I always think of is Memento, where it's got this completely backwards story structure that somehow works, and I never would've thought to do that before seeing that movie. I think some of the examples in your book, they may be able to do that for people who read it. So, just to give you a little... unlock that piece of your brain.

Liz Blazer: So, I haven't seen Memento in a while, but if I remember correctly, it's a three-act backward. It's a three-act, and it's a countdown because you are building, building, building, building, and it's also a high concept. So, those are things that I talk about, but I think for motion graphics, two of the most important structures that I discuss in the book, one is the beaded necklace, and I find that in motion graphics voiceover is a huge place that you're getting a lot of your information, or you're getting text on screen, but I hear a lot of voiceover. So, the beaded necklace is when music, sound or voiceover is holding all the chaotic visual elements together, and it's the string that it prevents the beads from falling.

Liz Blazer: So, if you have your structure laid out with that soundtrack, anything can happen, if that's your structure, because you're listening and following. Anything they say, you go with. The other one that I think is really important for motion is the puzzle. The puzzle is you're keeping your audience in the dark, and you're revealing bit by bit of information that comes all together in the end. So, in the final act or the final few seconds, something visually is going to happen that makes the other pieces at the beginning, "Ah, that makes sense." I see this a lot with logos. So, what happens is when it ends you're like, "Ah." You know it's the ending.

Joey Korenman: That's a great example. Okay. So, the beaded necklace one I really loved because we've actually seen a lot of these lately in the motion design industry. There was one a few years ago that Claudio Salas did called The Wisdom of Pessimism where the thread is this poem, and every shot is some sort of metaphor about what's being said, but it's done in a completely different style. It's almost like an exquisite corpse, like a bunch of different artists worked on it, and that's really common, and it's actually a great story structure for motion design because its lets you scale your team up without having to worry too much about a cohesive style, because-

Liz Blazer: Totally.

Joey Korenman: ... you've got this thread, and then the logo reveal, that is kind of the quintessential motion design thing. I mean, I've done hundreds of them, of there's a piece, there's another piece, there's another piece. What is it? It's the logo for whatever.

Liz Blazer: But you can do that conceptually with story, where you're like... Let's think of The Crying Game. That's a puzzle. We find out at the end, uh-oh, it's not a man. But the puzzle... Again, you can lay these over the three-act, and it's an additional structural tool that helps the audience at the end feel like, "Man, that's awesome. I was following along, and now I have this totally satisfied feeling at the end of the meal."

Joey Korenman: Yeah. So, I really, really recommend everyone read the book just for this stuff. I mean, there's so much more in it, but this was the part that... I was never taught this, and it's kind of one of the things like if you didn't somehow go to a school where they make you learn this stuff, you're I think less likely to read it. Everyone wants to learn how to do more After Effects tricks or get better at design and animation, and story sometimes gets left behind. Reading your book, it really hits home the importance of it. So, I think my final question for you, and thank you so much for being generous with your time-

Liz Blazer: I could do this forever, man.

Joey Korenman: Yeah. I have a feeling we could just sit here and chop wood all day. Okay. So, Liz... Actually, I'm going to call it Blaze. All right, Blaze.

Liz Blazer: All right.

Joey Korenman: So, I want to end with this. I want to hear what your thoughts are on the state of storytelling in our industry, given the fact that there are so many studios doing very, very, very, very short-form things that are Instagram stories, emoji packs, things that are, to use a word that I've heard from these studios themselves, they're disposable. They're not really meant to stick with you. They're meant to get your eyeballs for that 10 seconds, and they do that. That's a success. Is storytelling getting, I don't know, cheapened or anything like that?

Liz Blazer: Well, I think it's diluted, and I think that's great too. I think it's just a thing, and it's another package, another form, another deliverable. It's not my favorite form. I think it's over before you see it. It's almost like an expanded still, in a way. It's going to keep going, but we have to keep pushing back and making a space for other things, and sell to the people who are buying to our clients new stories and the future of storytelling, which is an incredible organization by Charlie Melcher, and they are studying how all this new technology's going to inform our way of telling stories, and how our graphics and our animation can be consumed through headsets.

Liz Blazer: Are the headsets going to turn into the sides of buildings or walkways? What ways are we going to be consuming stories? Yes, they're short. Yes, that's what the business wants. Yes, everybody's staring at their phone. That's fine. That's today, but what's tomorrow? We got to give them what they want, got to pay the bills. I want to pay the bills, but I also want to push them toward what's going to happen next year, next decade. You know?

Joey Korenman: Yeah, I'm thinking of that 6 Word Story. I mean, it seems like that's kind of an idea that helps navigate things like this, because you're going to have, at least on some of these jobs, a lot less time to tell a story, but you still think that even if you have a five-second little gif loop or something, you still think that it's possible to say something compelling?

Liz Blazer: I love gifs. I think gifs are gorgeous, and I think it's also a super interesting... The gif is a book-ending structure. It begins and ends at the same place, and where you go in the middle becomes this commentary. Right? So, I love the gif, and I love short form. I just think it's one little thing that is happening, yes, and I'm just hopeful that it's not going to be the only thing. Right? Because we're going to be seeing more and more sides of buildings that are TVs, and walkways. I don't know. I think that it's what's happening, yeah, and I'm just hopeful it's not going to make it so that everything has to be 10 seconds or less.

Joey Korenman: After this conversation ended, Liz and I talked for another 20 minutes, and I think it's pretty obvious that we have a similar sense of humor. I just had so much fun learning about Blaze and her history in animation. Check out Animated Storytelling, available on Amazon and probably wherever else you get your books. Check out the show notes on schoolofmotion.com for details. That is it for this one. Thank you so much, as always, for listening in. I don't know. Go outside.

ENROLL NOW!

Acidbite ➔

50% off everything

ActionVFX ➔

30% off all plans and credit packs - starts 11/26

Adobe ➔

50% off all apps and plans through 11/29

aescripts ➔

25% off everything through 12/6

Affinity ➔

50% off all products

Battleaxe ➔

30% off from 11/29-12/7

Boom Library ➔

30% off Boom One, their 48,000+ file audio library

BorisFX ➔

25% off everything, 11/25-12/1

Cavalry ➔

33% off pro subscriptions (11/29 - 12/4)

FXFactory ➔

25% off with code BLACKFRIDAY until 12/3

Goodboyninja ➔

20% off everything

Happy Editing ➔

50% off with code BLACKFRIDAY

Huion ➔

Up to 50% off affordable, high-quality pen display tablets

Insydium ➔

50% off through 12/4

JangaFX ➔

30% off an indie annual license

Kitbash 3D ➔

$200 off Cargo Pro, their entire library

Knights of the Editing Table ➔

Up to 20% off Premiere Pro Extensions

Maxon ➔

25% off Maxon One, ZBrush, & Redshift - Annual Subscriptions (11/29 - 12/8)

Mode Designs ➔

Deals on premium keyboards and accessories

Motion Array ➔

10% off the Everything plan

Motion Hatch ➔

Perfect Your Pricing Toolkit - 50% off (11/29 - 12/2)

MotionVFX ➔

30% off Design/CineStudio, and PPro Resolve packs with code: BW30

Rocket Lasso ➔

50% off all plug-ins (11/29 - 12/2)

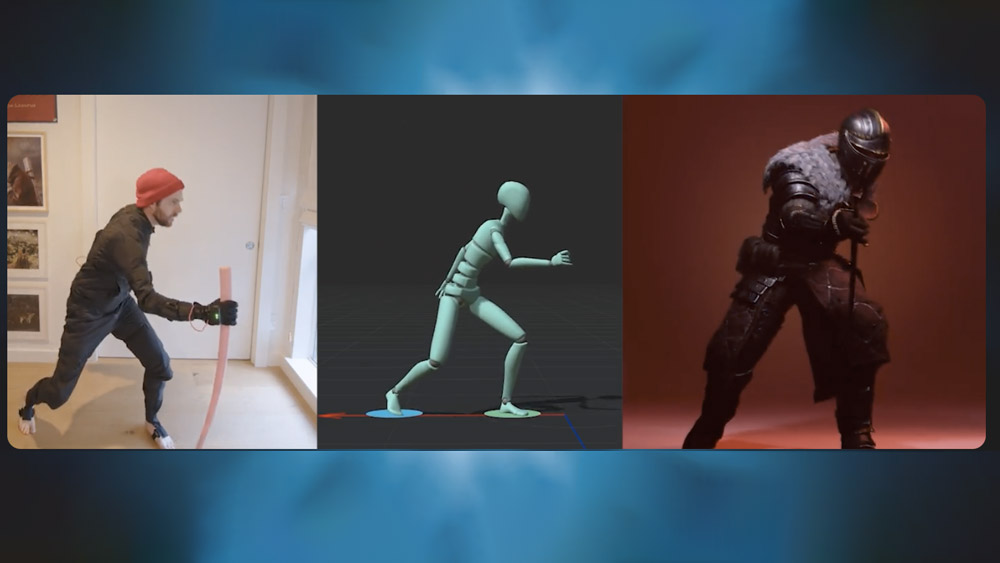

Rokoko ➔

45% off the indie creator bundle with code: RKK_SchoolOfMotion (revenue must be under $100K a year)

Shapefest ➔

80% off a Shapefest Pro annual subscription for life (11/29 - 12/2)

The Pixel Lab ➔

30% off everything

Toolfarm ➔

Various plugins and tools on sale

True Grit Texture ➔

50-70% off (starts Wednesday, runs for about a week)

Vincent Schwenk ➔

50% discount with code RENDERSALE

Wacom ➔

Up to $120 off new tablets + deals on refurbished items